For generations, winter in Korea has been inseparable from cod. As temperatures dropped, the cold-loving fish would migrate south through the East Sea, filling coastal waters and markets with one of the season’s most cherished ingredients. From home kitchens to neighborhood soup houses, cod signaled the arrival of winter meals meant to warm the body and restore energy.

Today, that familiar rhythm is beginning to falter.

A Sharp Decline Beneath the Surface

Cod populations along Korea’s southern coast have fallen dramatically in recent years. Provincial data from South Gyeongsang shows that catches plunged to roughly 42,000 in 2025, down from around 240,000 just three years earlier. Marine scientists and fisheries officials largely attribute the drop to warming ocean temperatures, which are disrupting the cold-water habitats cod depend on to survive and reproduce.

As seas grow warmer, cod are forced to migrate farther north or struggle to spawn successfully, shrinking the once-reliable fishing grounds that sustained coastal communities and seasonal industries.

Why Cod Matters to Korean Cuisine

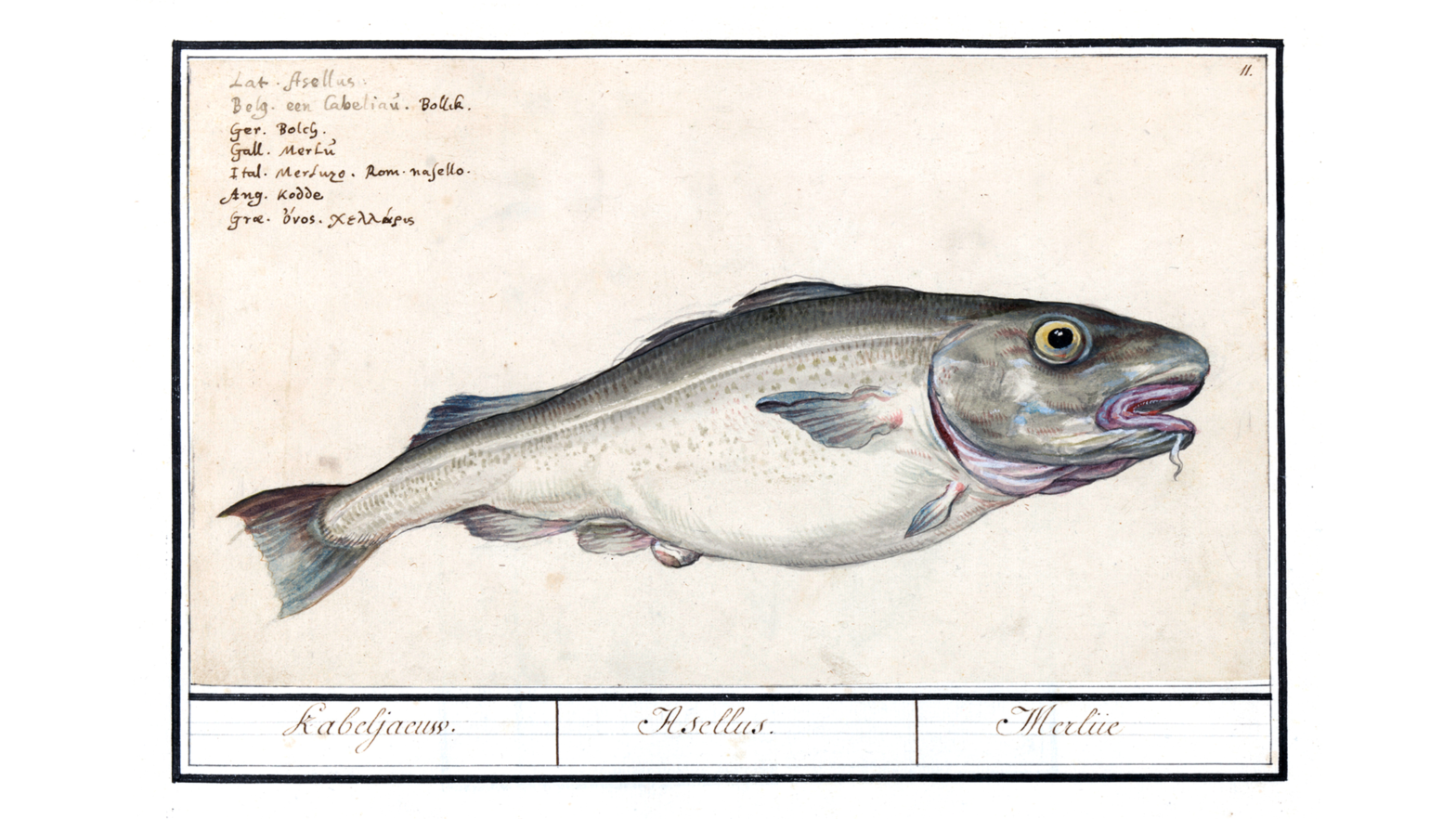

Cod holds a special place in Korean food culture not just because it is abundant in winter, but because of its culinary versatility. Its pale flesh is soft and flaky, releasing a clean, savory flavor that shines in broths. Unlike oilier fish, cod produces a light, clear soup with depth but no overpowering aroma — a quality that has made it a staple for generations.

Classic dishes such as daegu-tang, a bold, spicy cod stew, and daegu-jiri, a delicate clear soup, are winter essentials. These meals are often associated with recovery and renewal, commonly eaten as hangover cures or nourishing comfort food during the coldest months.

A Fish Used From Nose to Tail

One reason cod has remained so deeply embedded in Korean cooking is that nearly every part of the fish is valued. Beyond the fillets, cooks make use of the liver, gills and internal organs, ensuring little goes to waste. The milt, or reproductive glands, is especially prized in winter for its creamy texture and subtle richness, while the liver adds intensity to sauces and steamed dishes.

This full-use approach reflects both culinary ingenuity and a longstanding respect for seasonal ingredients.

Nutrition Built for Winter

Cod’s appeal also lies in its nutritional profile. It is high in protein yet low in fat, making it filling without being heavy. Packed with essential vitamins and minerals, it provides sustenance during colder months when the body craves warmth and energy. Its mild taste makes it accessible to all ages, from children to the elderly.

A Cultural Loss in the Making?

As cod stocks continue to shrink, concerns are growing that the fish may become less accessible — or even absent — from winter tables. Beyond ecological consequences, the decline threatens a deeply rooted food tradition tied to seasonality, health and shared memory.

Protecting cod is no longer just a matter of preserving a species. It is about safeguarding a piece of Korea’s culinary identity at a time when climate change is quietly reshaping what ends up on the plate.